The Near and Far Enemies of Equanimity

The Near and Far Enemies of Loving Kindness

The Near and Far Enemies of Compassion

The Near and Far Enemies of Sympathetic Joy

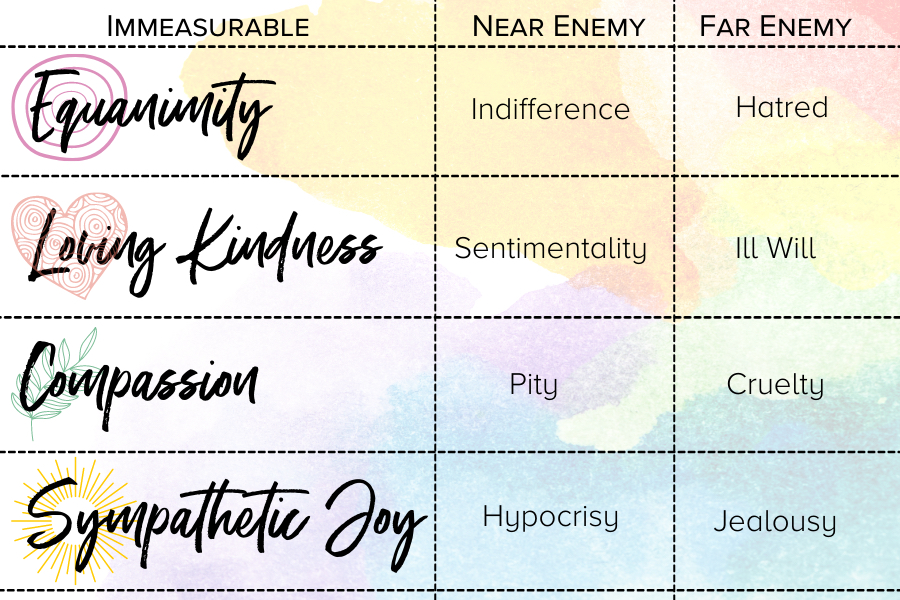

The Four Immeasurables, also called the Four Boundless Qualities, and the Four Brahmaviharas are the Buddhist virtues of Equanimity, Loving Kindness, Compassion, and Sympathetic Joy. Each virtue is accompanied by a practice. Together, they help us cultivate and feel connection. Shamata and Vipassana practice help us to see reality, the Four Immeasurables help us to feel our interconnected reality.

As though having three different titles isn’t confusing enough, each Immeasurable also has a Near and Far Enemy. Here they are in summary. Keep reading for detailed explanations!

The Near and Far Enemies of the Four Immeasurables, by Lama Tsomo

The Near and Far Enemies of Equanimity

Near Enemy: Indifference

Far Enemy: Hatred

Practice: Three-minute Introductory Shamata and Vipassana Practice with Lama Tsomo.

We begin with Equanimity . This seems distinct and clear enough. We practice Equanimity to expand our feeling of warm, caring connection to all beings, equally strong for every one of them. Its Far Enemy is an equally clear opposite. It’s that Buddhist classic, Attraction/Aversion–in other words, Preference. If we feel preference for some people over others—my brother, my friend, my ally—we’re obviously not practicing Equanimity. And if we are annoyed, angered, repulsed by some people, then we’re obviously not practicing Equanimity, either.

Of course, we all do feel preferences for some people over others. We feel attraction and love for some, and aversion toward others. This just means that we’re not buddhas yet, and we could do with some Equanimity practice. The good news is that it’s fairly obvious that when we’re feeling this Far Enemy, we’re far away from Equanimity. By definition, any of the Boundless Qualities and its Far Enemy can’t co-exist in our minds. They’re opposites. So, when we feel Preference, we’re clearly not feeling Equanimity, and vice versa.

Sometimes in my psychotherapy practice, a client would insult or accuse me during a therapy session. I could handle it with Equanimity; after the session I didn’t think about it again. Though I certainly cared about the person–I came to love every one of my clients–I wasn’t feeling strong Desire or Aversion toward them. On the other hand, if a family member or enemy were to say the same thing, I might very well be hurt or furious. The incident would live on in my head, causing me consternation every time I thought about it. And if someone I am especially close to does something particularly nice for me, I may feel more strongly motivated to nurture their well-being than I am the well-being of the ones who insulted me.

As we all know, love and hate are very close: intense feelings toward someone who is a central figure in our mental and emotional landscape. In either case—feeling hate toward anyone, or feeling love to the exclusion of, and to the detriment of, others—we would be in the territory of the Far Enemy of Equanimity. It was the Desire or Aversion driving us to express our anger or our gratitude that brought on the loss of Equanimity. Though this Far Enemy can be a real struggle to work with, its advantage is that at least it’s obvious.

The Near Enemy is less dramatic and less obvious. The Near Enemy of Equanimity is Indifference. You can fall into Indifference and stay there for a long time, rather smug that you’re feeling Equanimity … but you’re not.

Indifference is dressed in Equanimity’s “clothing,” but it feels different. It also has a different effect. “I don’t care” is not the same as “I care deeply, equally, and inclusively.”

Until his Christmas Eve epiphany, Ebenezer Scrooge treated everyone with equal indifference (he didn’t care that it was Christmas, he didn’t care that Tiny Tim was ill, he didn’t care that his long-time business partner had died, he didn’t care about the poor), but he wasn’t practicing Equanimity.

That’s still rather obvious, but there are much less obvious examples. How many times have you found yourself or others feeling pleased that they’re not upset by the angst around them? Or perhaps in our Equanimity practice we notice we don’t lean too far toward the people we prefer, congratulating ourselves on our restraint. If we look closely, though, we might be practicing Indifference rather than Equanimity. The exercise has become theoretical, and the feeling sense is lost altogether. Though it can look like Equanimity, it serves to separate us from the objects of our Indifference rather than join us in strong feelings of love.

Let’s take the practice of Tonglen, for example. In this case, Equanimity means feeling equally Compassionate toward whomever we’re thinking of (and as you’ll recall, by the end of the practice we’re usually thinking quite inclusively.) The word “compassion”, from the Latin, literally means, “to suffer with.”

When we start Tonglen practice, we develop the strong, passionate desire to take away the loved one’s suffering and to replace it with ultimate, lasting joy. The feeling is so strong that we’re often in tears, though often smiling at the same time, as we bring them ultimate, lasting happiness on the outbreath. Then we step that same compassionate feeling out to all beings, thus bringing Compassion together with Equanimity. This is what makes it a Boundless (instead of measured, with a boundary or limit) Quality. This is hardly Indifference. But beware, because Indifference can creep into your practice in all of the Four Boundless Qualities, not just with Compassion. That is exactly why the Buddha emphasized this distinction.

For any of the Four Boundless Qualities to be truly beyond measure, we have to feel each of them intensely, and without bias. That’s why Rinpoche always tells us to practice Equanimity first. I apply it to all the Boundless Qualities while I’m practicing them, stepping the rings out to include all sentient beings. That’s why I begin close in to those for whom I can easily feel strongly. That primes the pump of caring and connection and helps protect me from falling into Indifference. That allows my Love and Compassion to roll out strongly to all beings, with equal force. My feeling of loving connection increasingly approaches Boundless.

Imagine if we all felt as much love and compassion for everyone as we do for our best friend. How would the world look? Really play that out in your mind a bit right now.

Now imagine what would happen to your own tight grip on your identity—your ego—if you felt that strongly for everyone. How would you then feel about giving your spot in the checkout line to someone who seemed to be in even more of a hurry than you were?

The Near and Far Enemies of Loving Kindness

Near Enemy: Sentimentality

Far Enemy: Hatred, Ill Will

Practice: Six-minute Loving Kindness Practice with Lama Tsomo

The obvious opposite to Loving Kindness is Hatred, or its little brother, Ill Will. I hardly think you need an explanation of that one. Of course, the ability to dispense with Ill Will isn’t as easy as recognizing it when you see, or feel, it. That’s what the practice is for.

The classic Near Enemy to Loving Kindness is Sentimentality. Until my Buddhist training, I hadn’t heard that, but as soon as I did, I realized, “Aha! That’s exactly right!” Somehow, we do know that while Loving Kindness joins us in right relationship with another, Sentimentality subtly separates us. It’s more self-referential, and in the wave of Sentimentality we bathe ourselves in, we’ve lost sight of the presumed object of our feelings—the other human being. They’ve become a screen for our own maudlin movie.

I have a dear, childhood friend who’s often VERY sentimental about everything. She’s afloat in a sea of Sentimentality and revels in being carried about on its waves and tides. She’s been an extremely loyal friend through the years, but when I talk to her of my life and she swoons over some little thing I’ve mentioned, I don’t feel her love for me. It doesn’t feel like she’s responding to me, and I find no satisfaction or sense of joining in talking to her about my circumstances. Sad but true.

Instead, I feel like she’s doing two things: Using me to pat herself on the back for being a loving friend, and indulging in surges of drama, using my story almost like a TV show. “Using” being the operative word. TV shows are meant to entertain the audience. That’s what I feel I provide for her. No wonder visits with her feel less than satisfying for me. I believe that if she practiced true Loving Kindness, she would feel much more satisfied too, because she would feel truly connected to her friend. Unfortunately, she’s not able or even particularly willing to change this habit. I love her despite the Sentimentality, not in response to Loving Kindness.

Another Near Enemy of Loving Kindness is Conditional Love, a prevalent form of which—desire/clinging—is easily and often mistaken for true Love. The most popular arena for this little substitution is in romantic love. Especially during the first three years of a relationship, huge loads of endorphins, the pleasure chemical in our brains, are produced. (Many “recreational drugs” artificially trigger them—making them hard to resist and hard to abandon.) Endorphins are the original high, and we can stimulate them naturally with new romantic love. Of course, we’d desire as much of that as we can get, and cling to every opportunity. But even without the brain science, you knew that. As soon as I mention desire/clinging being mistaken for love, I’m sure you can think of examples in your own life.

In my early adult years, I was terribly guilty of this one. For me, it wasn’t even just the rush of the endorphins. On top of that, I was still looking for the lost warmth and closeness from my dad that I didn’t get as much as I wanted because he was working so much. Once that early stage of life passes, we can never fully make up for the missing critical pieces. That sure doesn’t stop us from trying, though. Again, and again, and again. Of course, we’re never satisfied. And of course, the other person recoils from our clinginess. I saw this happen again and again, in my own life, but couldn’t stop myself. At first, I didn’t even realize that my very clinging was driving the person away. It’s perhaps ironic that we all want to be needed, but we find neediness unappealing.

Important warning for practicing this method: I’d mentioned before that we Westerners might need to start with Loving Kindness for ourselves. This too, has a near enemy: self-centeredness. We’ve already got that one down. (As I once heard someone remark wryly, “I’m not much. But I’m all I ever think about.”) But it’s not the same as the universal, spacious, powerful Loving Kindness that we’ve been talking about. Instead of “Love thy neighbor as thyself,” it becomes, “Love thyself at the expense of thy neighbor,” or “Love thyself! Who cares about thy neighbor?” Oops! It seems to me that some people practicing and promoting pop psychology fall into this. Not exactly what the Buddha was encouraging.

The acid test for any of the Near Enemies is to see if it causes us to be more, or less, empathetic with fellow sentient beings; does it join us or part us? And self-centeredness, of course, is exactly what the whole of Buddhism is trying to help escape.

The Near and Far Enemies of Compassion

Near Enemy: Pity

Far Enemy: Cruelty

Practice: Eight-minute Tonglen or Compassion Meditation with Lama Tsomo

Let’s next turn our attention to Compassion. The obvious opposite feeling, the Far Enemy of Compassion, would be Cruelty. I don’t think I have to explain to you how Hitler and his friends were practicing something as far away from Compassion as possible. (It’s worth noting, by the way, that a lot of the less zealous “everyday” Nazis were practicing the Near Enemy of Equanimity: Indifference; they didn’t care what was happening around them, in their name.)

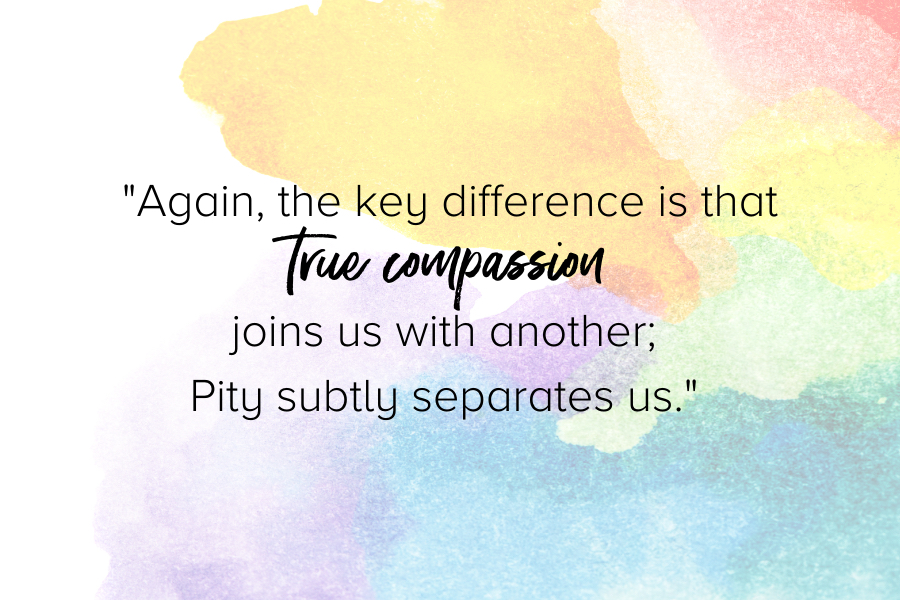

The Near Enemy of Compassion is Pity. As with the other Near Enemies, we can absolutely feel the difference on the receiving end. No one likes to be pitied, but we all appreciate Compassion. Why is that? Pity puts the recipient in a one-down position–by definition, breaching the goal of Equanimity. Pity disrespects them. If I’ve had a terrible accident and am seriously injured, I’m not comforted by someone saying, “There-there, you poor thing.”

Someone coming from genuine Compassion would be sensitive to what would feel good to me. They might ask me what I’d like, offer to get me something, or even just talk to me about something other than my condition. When I broke my foot, I could feel such people’s warmth, caring, and respect, without even a word said.

Ram Dass has spent many hours sitting with dying people and their families. He would often sit for an hour or two, not saying anything at all. But the quality of his strongly compassionate presence (no doubt felt through mirror neurons, morphic resonance, and who knows what else) was palpable. At the end of his time with the dying and their loved ones, they would often thank him profusely and go on about how much he’d helped them. Since he’d just been sitting there, “doing” nothing, he was a bit bemused. But he kept on with this practice, and it kept helping people. Again, the key difference is that true Compassion joins us with another; Pity subtly separates us. Deep connection with another probably won’t heal the dying, but it certainly can help us in almost any circumstance.

The Near and Far Enemies of Sympathetic Joy

Near Enemy: Hypocrisy

Far Enemy: Jealousy

Practice: Eight-minute Sympathetic Joy Practice with Lama Tsomo

Last but not least is Sympathetic Joy. The Far Enemy, naturally enough, is Jealousy, competitiveness. As a matter of fact, when we feel jealous or competitive with another, the Buddha instructed us to cultivate Sympathetic Joy as the antidote.

Let’s talk for a minute about the Far Enemy before moving on to the Near Enemy, because even though the Far Enemy is easier to spot, it can be awfully hard to work through. In that case we’re going to be throwing someone out of our heart, thereby making Sympathetic Joy less than Boundless. Instead, our own heart shrinks.

Have you ever felt less than Sympathetic Joy when someone else just bought a nice car and you couldn’t? Or when someone else just found a wonderful life partner while you were still unhappily single? Perhaps you have trouble feeling a whole lot of joy—maybe any joy at all—for them because, let’s face it, you don’t get to have that same thing. But does their having joy keep you from having it? Will your refusing to be happy for them help you to get that car or sweetie? Even if you can’t celebrate those things for yourself, how will it hurt anything to celebrate it for them? Heck, at least you get to celebrate it for someone. Lots of people who are frustrated at finding a sweetie get all sappily happy at romantic movies. If we can be happy for some imaginary people getting such things in movies without resenting them for it, why not in real life?

How about a case where someone you were competing with beat you out for first place? Of course, it’s all the more challenging to be happy for them. I wouldn’t try this one right away. But someday you might challenge yourself with this one. You could ask yourself again, “Now that I already lost first place, how will it help me to resent the person who won it?” Just from a purely selfish point of view, resenting them won’t get you first place after all. Again, given that you already didn’t win you could ask yourself, “How will it hurt anything to celebrate for the winner?” Again, at least that way you get to celebrate for someone, instead of just feeling crummy.

The Near Enemy is Hypocrisy—feigned appreciation of the person who’s having good fortune. I hardly need to explain the difference between feigned Sympathetic Joy and the real

thing. The difficulty here is in honestly admitting to faking it. Perhaps we do this just to make ourselves feel or look like a good person—a good sport. But even if we aren’t secretly jealous—the Far Enemy—we might, for example, be passing judgment secretly on their good fortune not being important, or their not being worthy of it.

One conversation with my father, many years ago, illustrates this near enemy. One day I told him that I’d been accepted for a two-month apprenticeship program at an excellent acupressure clinic in California. They’d never offered such an apprenticeship before, but they liked the idea and were willing to design one for me. I was thrilled! My father smiled faintly: “That’s nice, honey.” He said the right words, but rather than feeling that my joy was shared, I felt a pinprick in my balloon of excitement. Poof! Though he was smiling and saying nice words, his response served to separate us, not to join us in loving connection.

I knew my father didn’t believe in any sort of alternative medicine. But that wasn’t the point. I wasn’t asking for him to share my opinion on the merits of acupressure; I wanted him to share my joy in receiving an honor and an opportunity that delighted me.1

How do we feel true Sympathetic Joy for someone when we’re judging what they’re happy about, don’t like them, or feel competitive with them? It always helps me to remember that the person experiencing joy—even if it’s not for reasons that would make me at all joyful—is wandering around in Samsara, just as confused as I am. They want to be happy as much as I do. They want to avoid suffering just as much too. If they’ve found a moment of joy in this bed of thorns, why not be happy for them? It doesn’t hurt me one bit to feel that joy.

In fact, it feels better than wishing they were miserable, or one-down. It feels better to me. In fact, whenever I tune in to the underlying “we-ness” of our humanity, our sentient beingness, I feel a relaxing in my heart. I breathe easier—no doubt because I’ve just fallen into right relationship with that person. In this small way I’ve come closer to the way things truly are, closer to home.

I’ve found that by tuning in to our common ground, I can practice any of the Four Boundless Qualities even with people I dislike the most, even people who have spent years waging campaigns against me. But remember, these challenges are not for our first forays into these practices. Just as we push the envelope gradually when we do hamstring stretches, we push the envelope gently but consistently with these practices.

Paradoxically, it’s this gentle, gradual approach that yields the fastest results. If I do gentle hamstring stretches twice a day, every day for a short time, in a matter of weeks I can touch my palms to the floor. If I only do them once a week, I make no progress. Scientific studies have shown that after a few weeks of daily practice, people’s capacity for loving connection, in various forms, improves dramatically. Stephen Post and Jill Neimark’s book Why Good Things Happen to Good People offers discussion and examples of this principle.

People’s actions during the day change too. As you continue to practice, you’ll no doubt also notice a difference for, and in, yourself. Others on the outside will notice it, but you’ll probably notice even more difference on the inside. After training in these four ways of feeling more connected, less alone, how could you not help but feel that way, ongoing? And remember, there’s no rule that says you have to stop when you get off the cushion. Just as with stretching hamstrings, you can speed up these changes by using these four methods whenever you think of it during the course of daily life.

To begin or rejuvenate your meditation practice, join a free eCourse today!

Love and compassion are innate qualities that can be nurtured, yet modern life often distracts us from them. The Four Immeasurables, or Boundless Qualities in Tibetan Buddhism, provide a path to open our hearts, deepen connection, and dissolve isolation, helping us rediscover our shared humanity. Learn more about these innate qualities in our upcoming Four Immeasurables Retreat, Feb 21 -23, 2025! Online and in-person in Hot Springs, MT.

Join us this September 11-14 for our online and in-person Green Tara Retreat. Deepen your connection with Green Tara, the swift and fearless embodiment of awakened compassion. Spots are limited, register today!

Get meditations, teachings, and more in your inbox.

STart your journey

The Four Immeasurables Retreat

Love and compassion are innate qualities that can be nurtured, yet modern life often distracts us from them. The Four Immeasurables, or Boundless Qualities in Tibetan Buddhism, provide a path to open our hearts, deepen connection, and dissolve isolation, helping us rediscover our shared humanity. Learn more about these innate qualities in our upcoming Four Immeasurables Retreat, Feb 21 -23, 2025! Online and in-person in Hot Springs, MT.